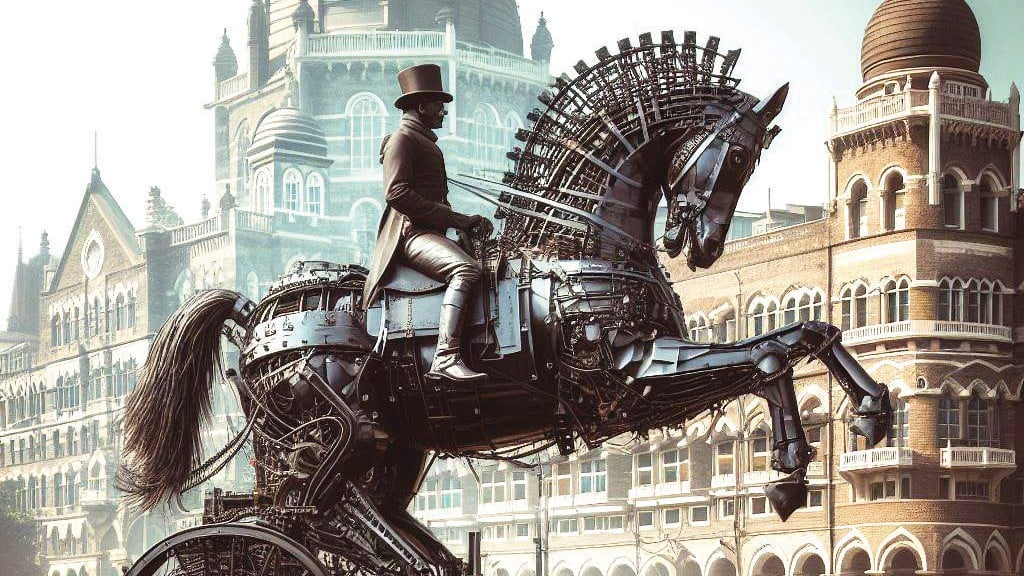

steam·punk [‘sti:mp ŋk] – noun

A sub-genre of science fiction in an historical or anachronistic setting, typically featuring steam-powered machinery rather than advanced technology

—

With the Kala Ghoda Arts Festival 2025 ongoing (25 January–5 February), Mustansir Dalvi takes quixotic licence with his column on urban affairs to present a playful reimagining of the Kala Ghoda’s origins, placing its emergence in steampunk sci-fi located in late 19th century Bombay.

Please be advised: this is a work of fiction; names, characters, places, incidents, timelines are the products of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental:

The automaton was something of a dark horse. Arriving unannounced outside the Taj mounted on a Ford T, both horse and rider were bespoke mechanicals, rivetted together to welcome those disembarking from transcontinental liners, and climbing up the steps to the Gateway of India for the first time into a new city.

Sensing them incoming, the horse would crank up, rearing its front legs to its full height of 18 feet and whinny, steam whistling from its nostrils like Smaug the dragon.

The equestrian robo-gent, whose hooter some said resembled that of the current Prince of Wales, would raise his hand, tip his top-hat and loudly declaim in a pre-recorded voice: “Baaaaambaayy! Welcome to Baaaambaayy!”, scaring matrons and biddies lately of Birmingham and Stepford half to death.

The motor car would then run circles around them, honking wildly, herding them in the direction of the Taj, and away from William Booth Green’s Mansions. Few realised this at the time, but the horse-ford was a front in the final negotiations by the Tatas to acquire Green’s Hotel.

This ungodly contraption was a final bit of arm-twisting. Soon, the better dressed expatriates would be gaslit into making their way to the more palatial offerings, while the smaller hotel would get the hoi-polloi: carpetbaggers, china salesmen and assorted ragtags and bobtails. Within the year, Green’s was acquired by the Mota Bhai, and all this was as if nothing had happened.

Which led to the question of what was to be done with the mechanoid. One of the niggling issues plaguing its operators was that the automaton had started to gather an unwanted fan-base: urchins from as far away as Gai Wadi and Umerkhadi would come to the Palva Bunder every evening to chase behind the Ford T like the grubby tail of Halley’s comet.

Deep in the dining rooms of the Taj, string-quartets would be thrown off rhythm by sudden, piercing shouts in Kokani: “Ghorra aila ré!”

The contraption soon went by the name: काळा घोडा. Middle-management at the Taj (to keep themselves relevant) now suggested cornering the clientele of the other significant competition— the Europeans-only Watson’s Esplanade Hotel. The wide plaza outside it, with Rampart Row on one side and the lawns of the new museum on the other would provide ample space for the horse-car to tootle away and corral guests in the direction of the Gateway.

The Watson was also considered to be at its lowest presently, having been leased to local owners, Messrs. Sardar Abdul Haq, Diler ul Mulk, and Diler ul Daula for the next thousand (minus one) years one) years. So, on a balmy Boxing Day, it came to pass that the Kala Ghoda began its rounds on a new beat, outside the Esplanade Hotel.

Sleeping guests were startled awake by steam whistles and phonograph exhortations: “Baaaaambaayy! Welcome to Baaaambaayy!” Every inmate, shaven, unshaven or in the process of shaving emerged on the long cast-iron balconies of the hotel.

Crows perched on its railings took to wing, squawking in protest. Every eye peered downwards at the motorgharry mounted with horse and hat-raising rider. “God save the Queen!” remarked a wag from the upper floors. “And his anointed Prince Ted!” added a guest to general tittering. Messrs. Haq, ul Mulk, and ul Daula were not amused. This steam-powered sideshow was much worse than Indian Rope Trickwallahs who set up tokris below the balconies until the pattahwallahs were sent out to shoo them away.

By New Year’s Eve, the decline in bookings had become visible. Guests coming down from the Gateway were seen taking U-turns, choosing instead the Palace, to the dismay of owners, waitresses, cooks and shoe-shine boys at the Watson’s. Messrs. Haq, ul Mulk, and ul Daula wrung their hands, but bided their time.

Then, on 31 December, at the stroke of the midnight hour, when Bombay awoke to ship’s flares, fireworks and general hoohaa, when horse and horsemen was plying its trade most vigorously, with the constant ear-worm: “Baaaaambaayy! Welcome to Baaaam…” the whole shebang fizzed to a stop, sparks and smoke (not steam) spurting from all orifices. The Kala Ghoda went kaput.

On the new year’s first afternoon, police from the chowky on Palton Road were called to investigate the scrap heap blocking traffic. A small operation was mounted to shift it a few feet away and allow trams from Colaba to Victoria Terminus to resume.

The car was dismantled from its burden by mechanics from the Bombay Cycle & Motor Agency Ltd. (Opera House), and the Ford towed away by ox-cart for further diagnostics. Now repositioned on the curb, the horse’s arse faced due south, in the direction of its makers (by providence, not intent). And there remained, permanently silenced, rusting with every Bombay monsoon.

Tourists and riffraff alike clambered all over it, whooping like cowboys: “Ghorra aila ré!”

Postscript:

The Bombay Cycle & Motor Agency divined the death of the automaton due to a banana in the tailpipe, that led to a domino effect, resulting in multiple organ failure. No aspersions were ever cast on Messrs. Haq, ul Mulk, and ul Daula.

The Ford T was repaired, but not the Ghoda, nor the Rider. The Rajah of Dhanrajgir spotted the vehicle at the Agency and made them an offer they could not refuse. In any case, no one had come forward claiming ownership of either car or cargo.

To the chagrin of all at the Taj, the Rajah would proudly flaunt his Ford T along the sea-edge outside the Palace each evening he was in town, a new princely swaar, sans ghoda. The former mechanoid remained in-situ for half a decade, giving both focus and a name to the place outside the Watson. Trams would display the location on their fronts and gharrywallahs would happily bring you to the Watson’s if you said Kala Ghoda.

Richard Temple, newly appointed Governor of Bombay, sought public approval by raising horse and rider high on a stone pedestal with plaques in his name, and formally announced that this was the statue of Edward, Prince of Wales.

An unauthorised flea market has since emerged around the statue, usurping its name. In the last week of every January, the perimeter of the Kala Ghoda Plaza is cordoned off with stalls. Art that wouldn’t make the first cut in Bombay’s salons is displayed. The inner chowk gets filled with performing monkeys, madariwallahs and associated malarkey. Ladies from as far away as Parel and as near as Colaba descend on the grounds around the horse, seeking bargain buys of sweetmeats, scones, sewing kits and nighties.

MUSTANSIR DALVI was the longest serving Professor of Architecture in the University of Mumbai. He is a trustee of Art Deco Mumbai